This novel, which is now well over two decades old, always fascinated me (for admittedly prurient reasons), but for some reason I never got around to reading it until now. What finally got me moving was learning that Netflix was producing a film version. I knew I would probably get around to seeing that, which would spoil the story. And original novels tend to be better than their adaptations.

This novel, which is now well over two decades old, always fascinated me (for admittedly prurient reasons), but for some reason I never got around to reading it until now. What finally got me moving was learning that Netflix was producing a film version. I knew I would probably get around to seeing that, which would spoil the story. And original novels tend to be better than their adaptations.

The story concerns a middle-aged couple who head off to their private summer house to try and inject some passion back into their marriage. Gerald handcuffs his wife Jessie to the bedposts, with her permission (something that probably seemed a lot racier in the 1990s than it does now). Unfortunately he dies, leaving Jessie confined and alone, with no hope of rescue.

None of the above is much of a spoiler, as the majority of the story takes place with Jessie in cuffs. You might wonder how the author could maintain the reader’s interest, with so little actually happening. Well, there are some things that do physically occur in the bedroom, but the bulk of the action takes place inside Jessie’s head. Her emotions (panic, terror, despair) are described vividly and realistically. But we also take a journey into the past, where Jessie (aided by a part of her subconscious that she embodies as an old friend) revives some repressed memories of childhood trauma.

Some criticisms. The first half of the novel drags. King is overly verbose in describing the psychological state of the protagonist, and at times I was impatient for something to happen. But ultimately the story finds its feet and comes to a satisfying conclusion. The one part that lacked realism for me was the memory block. Child abuse is never to be taken lightly, but there are real children who suffer far greater things than Jessie, who carry those memories throughout their lives. In reality, it takes a lot for a child to remove an event from conscious awareness. King makes a huge melodramatic leap here, for the sake of getting his story from A to B, and it feels false.

Overall, Gerald’s Game is a worthwhile read. The Netflix movie is a faithful adaptation that does justice to the original novel (which you should read first).

The full title of the book is The Gentleman Downstairs and Other Satanic Parables and Fables. It contains 67 stories, each one short enough to fit on a single page, each one illustrating an aspect of the philosophy of the Chruch of Satan. The book is meticulously annotated with references to literature written by the church’s founder,

The full title of the book is The Gentleman Downstairs and Other Satanic Parables and Fables. It contains 67 stories, each one short enough to fit on a single page, each one illustrating an aspect of the philosophy of the Chruch of Satan. The book is meticulously annotated with references to literature written by the church’s founder,  Notorious atheist Christopher Hitchens has written this short volume, subtitled “Mother Teresa in Theory and Practice” as a critique of the enigmatic Catholic nun that everyone knows so well – or do they? My opinion of Mother Teresa, prior to reading this book, was stereotypically positive, informed only by the TV news. I don’t like Christianity, but regardless of one’s religion (or lack thereof), it is possible to live a life of selfless devotion to others. Few of us choose that path, but if anyone shines brightly in this regard, it’s got to be Mother Teresa, right?

Notorious atheist Christopher Hitchens has written this short volume, subtitled “Mother Teresa in Theory and Practice” as a critique of the enigmatic Catholic nun that everyone knows so well – or do they? My opinion of Mother Teresa, prior to reading this book, was stereotypically positive, informed only by the TV news. I don’t like Christianity, but regardless of one’s religion (or lack thereof), it is possible to live a life of selfless devotion to others. Few of us choose that path, but if anyone shines brightly in this regard, it’s got to be Mother Teresa, right? Carl Jung, who is known for an approach to psychology known as psychoanalysis, was a very prolific writer. It would be nearly impossible for the interested reader to collect every volume he wrote, so Anthony Storr has put together this 400-page compendium of excerpts in an attempt to give the reader a comprehensive overview of Jung’s concepts. Some of these are: the idea of the unconscious, archetypes, and dream analysis.

Carl Jung, who is known for an approach to psychology known as psychoanalysis, was a very prolific writer. It would be nearly impossible for the interested reader to collect every volume he wrote, so Anthony Storr has put together this 400-page compendium of excerpts in an attempt to give the reader a comprehensive overview of Jung’s concepts. Some of these are: the idea of the unconscious, archetypes, and dream analysis. I started reading this novel because of its status as a classic, but I must confess I knew nothing about its theme. As the story got underway, I had the distinct feeling that this was going to be a thoroughly depressing tale about reflections on the horror of war. Not my cup of tea. Imagine my surprise when the story made a weird tangent into Twilight Zone territory. The narrator, Billy Pilgrim, becomes unstuck in time. What I mean is, one second he could be in the trenches of World War II, and the next he could be cuddling up to the woman he married after the war. Two days after that, he could be on exhibit in an extraterrestrial zoo, where he spent some time after being abducted by aliens. Then he might be back in the war. He has no control over what point in time his consciousness leaps into, or when these jumps are going to occur, but his weird condition gives him a perspective on time that allows him to see “the present” as more than just a single knife-edge that exists at only one point in time and is always racing forward. His alien captors, the Tralfamadorians, live in four dimensions all at once, seeing every moment of time as the present. When events happen, good or bad, their reaction is always “So it goes.”

I started reading this novel because of its status as a classic, but I must confess I knew nothing about its theme. As the story got underway, I had the distinct feeling that this was going to be a thoroughly depressing tale about reflections on the horror of war. Not my cup of tea. Imagine my surprise when the story made a weird tangent into Twilight Zone territory. The narrator, Billy Pilgrim, becomes unstuck in time. What I mean is, one second he could be in the trenches of World War II, and the next he could be cuddling up to the woman he married after the war. Two days after that, he could be on exhibit in an extraterrestrial zoo, where he spent some time after being abducted by aliens. Then he might be back in the war. He has no control over what point in time his consciousness leaps into, or when these jumps are going to occur, but his weird condition gives him a perspective on time that allows him to see “the present” as more than just a single knife-edge that exists at only one point in time and is always racing forward. His alien captors, the Tralfamadorians, live in four dimensions all at once, seeing every moment of time as the present. When events happen, good or bad, their reaction is always “So it goes.” This volume brings together a collection of speeches and essays by the famous philosopher Bertrand Russell. They are all, directly or indirectly, about the topic of religion. In the titular essay, the author explains his reasons for being unconvinced by Christianity. In contrast to the typical view that Jesus was a good man but not the Messiah, Russell has no qualms about suggesting that he is not as good or as wise as we often make him out to be. He provides some compelling examples from the gospels, and makes an interesting comparison between the characters of Jesus, Socrates and Buddha, with Jesus seeming rather crude by comparison.

This volume brings together a collection of speeches and essays by the famous philosopher Bertrand Russell. They are all, directly or indirectly, about the topic of religion. In the titular essay, the author explains his reasons for being unconvinced by Christianity. In contrast to the typical view that Jesus was a good man but not the Messiah, Russell has no qualms about suggesting that he is not as good or as wise as we often make him out to be. He provides some compelling examples from the gospels, and makes an interesting comparison between the characters of Jesus, Socrates and Buddha, with Jesus seeming rather crude by comparison. While everyone’s feeling naughty for reading E.L. James’s 50 Shades of Grey these days, I thought I would instead delve into something by the man who gave sadism its name. My fascination with reading Philosophy in the Bedroom actually stems from the fact that I’ve got a soft spot for an old Jess Franco movie called Eugenie, starring the gorgeous Maria Rohm. According to the film’s opening credits, it’s based on the de Sade book here under review. The story is simple: a rich and powerful woman, Madame de Saint Ange, with her brother, Le Chevalier de Mirval, take a naive teenage girl, Eugenie, under their wing and proceed to give her an “education” in the ways of being a libertine, over the course of a weekend. While Franco’s movie does little more than tease the viewer, the original work is quite a different beast.

While everyone’s feeling naughty for reading E.L. James’s 50 Shades of Grey these days, I thought I would instead delve into something by the man who gave sadism its name. My fascination with reading Philosophy in the Bedroom actually stems from the fact that I’ve got a soft spot for an old Jess Franco movie called Eugenie, starring the gorgeous Maria Rohm. According to the film’s opening credits, it’s based on the de Sade book here under review. The story is simple: a rich and powerful woman, Madame de Saint Ange, with her brother, Le Chevalier de Mirval, take a naive teenage girl, Eugenie, under their wing and proceed to give her an “education” in the ways of being a libertine, over the course of a weekend. While Franco’s movie does little more than tease the viewer, the original work is quite a different beast. The reason I read this novel was because of the author’s introduction, part of which I now quote:

The reason I read this novel was because of the author’s introduction, part of which I now quote: I was especially attracted by the title of this volume because I’ve noticed that spiritual teachers have an unfortunate tendency to promise a lot more than they can actually deliver – Eckhart Tolle with his Zen-like persona being a prime example. I don’t believe in total freedom from suffering; that’s just not realistic. But “ten percent happier” is a phrase I can work with, because it suggests that ordinary human consciousness can be improved rather than transformed.

I was especially attracted by the title of this volume because I’ve noticed that spiritual teachers have an unfortunate tendency to promise a lot more than they can actually deliver – Eckhart Tolle with his Zen-like persona being a prime example. I don’t believe in total freedom from suffering; that’s just not realistic. But “ten percent happier” is a phrase I can work with, because it suggests that ordinary human consciousness can be improved rather than transformed. I don’t read every Stephen King novel that comes out (because he’s too prolific for his own good), but this one attracted me because religion is a topic that I find endlessly fascinating. I consider myself a survivor of the brainwashing exercise of my youth and early adulthood.

I don’t read every Stephen King novel that comes out (because he’s too prolific for his own good), but this one attracted me because religion is a topic that I find endlessly fascinating. I consider myself a survivor of the brainwashing exercise of my youth and early adulthood. Novelisations are a thing of the past – the distant past. They were useful in the days when hardly anyone owned a VCR (that’s video cassette recorder, since the term is no longer in common usage). Back then, the only chance of rewatching a movie was to wait until it was televised. So we had novelisations as a means of re-experiencing our favourite films. But since everything is now available inexpensively on DVD or blu-ray, novelisations are an irrelevance.

Novelisations are a thing of the past – the distant past. They were useful in the days when hardly anyone owned a VCR (that’s video cassette recorder, since the term is no longer in common usage). Back then, the only chance of rewatching a movie was to wait until it was televised. So we had novelisations as a means of re-experiencing our favourite films. But since everything is now available inexpensively on DVD or blu-ray, novelisations are an irrelevance. My first inkling that there was something wrong with our typical ideas about Satan came as a result of reading the Bible in its entirely. Until one does that, one is usually blind to the fact that Satan is hardly in the Old Testament at all. And when he is mentioned (primarily in the Book fof Job), he doesn’t seem to be the same guy that Christians are familiar with. He’s not the head of a kingdom of fallen angels in opposition to God. Instead, he’s keeping company with the regular angels. And he doesn’t step out of line. When God gives him instructions, he carries them out to the letter. The only “satanic” thing about him is the fact that he has a dirty job; he’s a sort of prosecutor. When God boasts about how much Job loves him, Satan is inclined to be sceptical, claiming that Job is only playing nice because God plays nice. “Take away the benefits and Job will curse you,” says Satan. And so the trials of Job begin.

My first inkling that there was something wrong with our typical ideas about Satan came as a result of reading the Bible in its entirely. Until one does that, one is usually blind to the fact that Satan is hardly in the Old Testament at all. And when he is mentioned (primarily in the Book fof Job), he doesn’t seem to be the same guy that Christians are familiar with. He’s not the head of a kingdom of fallen angels in opposition to God. Instead, he’s keeping company with the regular angels. And he doesn’t step out of line. When God gives him instructions, he carries them out to the letter. The only “satanic” thing about him is the fact that he has a dirty job; he’s a sort of prosecutor. When God boasts about how much Job loves him, Satan is inclined to be sceptical, claiming that Job is only playing nice because God plays nice. “Take away the benefits and Job will curse you,” says Satan. And so the trials of Job begin. A couple of years ago I was listening to a debate by Sam Harris, when he made a remark about consciousness being the one thing that you absolutely cannot declare is an illusion, because consciousness is the very ground from which you come to know everything else. This was not the sort of thing you hear from a typical atheist; atheists tend to be materialists who do their best to ignore the profound mystery of consciousness.

A couple of years ago I was listening to a debate by Sam Harris, when he made a remark about consciousness being the one thing that you absolutely cannot declare is an illusion, because consciousness is the very ground from which you come to know everything else. This was not the sort of thing you hear from a typical atheist; atheists tend to be materialists who do their best to ignore the profound mystery of consciousness. This is the first novel by science fiction author John Christopher (although he did publish a short story collection before this), who is most famous for

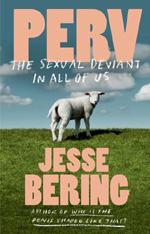

This is the first novel by science fiction author John Christopher (although he did publish a short story collection before this), who is most famous for  Psychologist Jesse Bering first hit my radar in 2012, when I saw an interview with him conducted at the Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2012 (see below). In this he talks about the case of an unfortunate young teenager who discovered his father’s medical textbook. This book featured nude photographs of women, which the boy used to aid his first attempts at masturbation. However, these women also happened to be amputees. One can understand how the boy may have been able to feel excitement at witnessing the forbidden areas of a woman’s body while also being able to disregard the missing limbs. However, if you know something about the unconscious mind, it tends to forge associations without us being aware of it. This is how the boy ended up with what is termed paraphilia – a sexual attraction towards something outside of the bounds of what is usually considered sexual. And he was seemingly stuck with it for life. Odd as it sounds, amputees turned him on more than full-bodied women.

Psychologist Jesse Bering first hit my radar in 2012, when I saw an interview with him conducted at the Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2012 (see below). In this he talks about the case of an unfortunate young teenager who discovered his father’s medical textbook. This book featured nude photographs of women, which the boy used to aid his first attempts at masturbation. However, these women also happened to be amputees. One can understand how the boy may have been able to feel excitement at witnessing the forbidden areas of a woman’s body while also being able to disregard the missing limbs. However, if you know something about the unconscious mind, it tends to forge associations without us being aware of it. This is how the boy ended up with what is termed paraphilia – a sexual attraction towards something outside of the bounds of what is usually considered sexual. And he was seemingly stuck with it for life. Odd as it sounds, amputees turned him on more than full-bodied women.